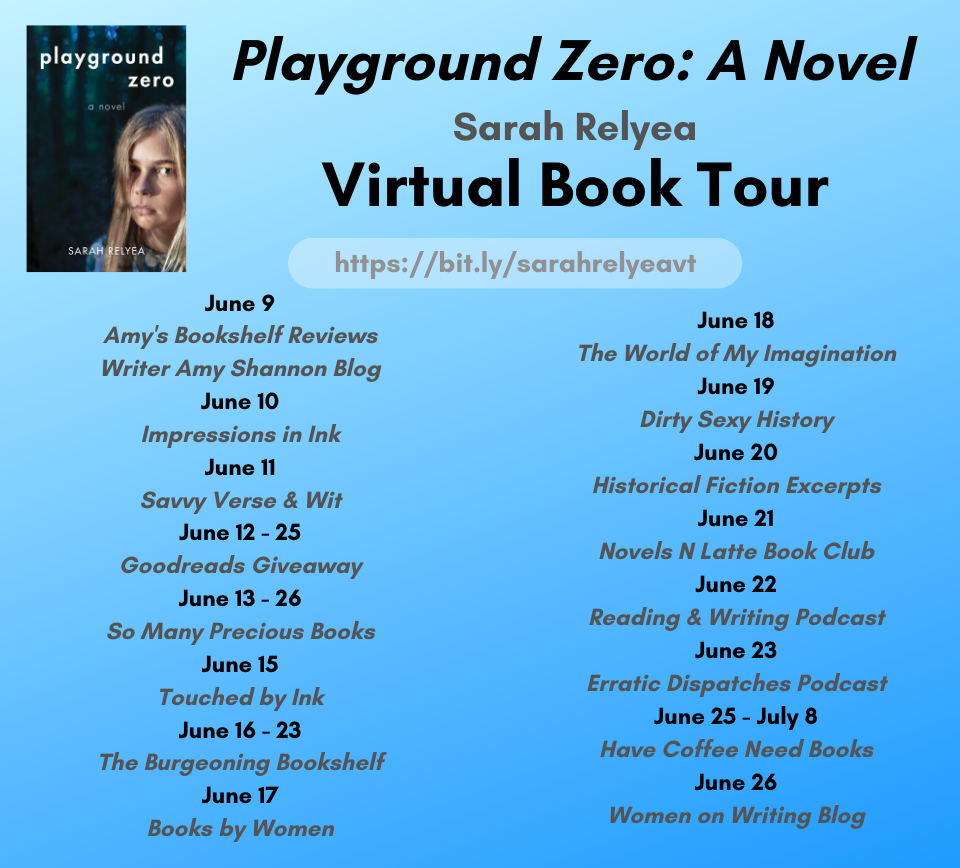

Note from Nicole: I am so excited to have Sarah Relyea here today! Make sure you check out her book and show her some love. She has an excellent post about writing a pandemic novel. Perfect timing!

Enough has happened in the last three months to keep a good writer busy for years. It’s as though we’ve been frozen in the moment, as calamitous events pass before our eyes. Since mid-March, when the pandemic really hit, I’ve been following the ghastly parade from a third-floor apartment in Brooklyn, New York. Like everyone else these days, I’m feeling overwhelmed and struggling to get things done. It’s not what you’d imagine, though. I’m not retreating into my mind and surrendering the world—rather, I’m embracing it. The city’s still in quarantine, but tomorrow is pounding on the door, and the lock is breaking as I type. I can’t ignore it.

Writing fiction during the pandemic is a challenge. Events have outrun imagination, and our former hopes—even our former fears—have been swept away. One day COVID-19 simply appeared, as though a sci-fi movie had burst from the screen and gone rogue. No one could follow the tangled genius of the plot. For days or weeks, we wondered who and where the bad guys were. We struggled to understand subplots featuring bats, asymptomatic carriers, and virology labs; we blamed each other. Hungry for good news, we cheered Superman in a lab coat.

Alone in the Crowd

I’ve long been interested in—and wary of—crowd behavior. And strangely enough, even while sheltering at home, I’ve been thinking about crowd responses. When unseen forces suddenly permeate our world, compelling us to cancel our normal activities, everything feels newly significant. A walk in the park becomes a foray through another country, where I’m surrounded by strangers—yesterday’s friends and neighbors!—with baffling habits. I struggle to understand new body language. How close can I stand to that person? What do her angry hand signals convey? Meanwhile, cross-cultural facial expressions—a smile or a scowl—communicate nothing, because we’re wearing masks.

We’ve all been strangers somewhere, feeling the wary glance of people uncomfortable with who we are, how we dress, and how we present ourselves. With luck, we’ve also found unlooked-for camaraderie. Now the pandemic has made us strangers everywhere—even in our own neighborhoods.

A Pandemic Novel

I may never write a pandemic novel. But I’m sure that I will use aspects of the pandemic world—the warping of human relations; the forging of unlooked-for connection—in whatever I do write. How could I forget zoom yoga and Kate Lynch’s ambulance meditation, as EMS sirens wail through the streets? Or zoom Bible study and church neighbors making music on the stoop? Or the Yemeni-American deli owner who risked COVID-19 to sell me newspapers and coffee?

Maybe I’ll drop my characters into a war-torn country, or maybe I’ll send them on a Mardi Gras parade that goes insanely wrong. After all, I’ve seen plenty of fear and masks. Remember—a novel creates an imaginary world, and a pandemic novel need not include an actual pandemic. As DJ Taylor suggests, fiction works by stealth; it deals in possibility—things that could happen in a world that could exist. As a novelist, you must not only document what’s happening; you must also feel it, absorb it, and be changed by it.

Only then will you develop an inner judge—not a censor but a judge, the part of you that administers truth serum as you write. The part that tells you what could happen—and what could never be.

Sarah Relyea is author of the historical novel, Playground Zero (She Writes Press, 2020), a coming-of-age story set in Berkeley in the late 1960s. Her first book was the nonfiction Outsider Citizens: The Remaking of Postwar Identity in Wright, Beauvoir, and Baldwin. Follow Sarah on Facebook and Goodreads.

Thank you for hosting this guest post!